Development & Life In The Village

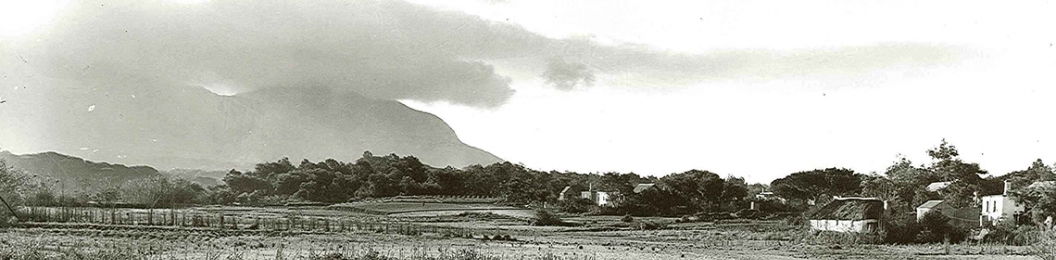

After subdivision in 1881, the area of lower Claremont had been further developed until there were about 100 cottages, mostly in the vicinity of Buchanan and St. Mathew’s Road (now First and Second Avenue) all owned by Henry Arderne in 1896. The area was even briefly referred to as “Ardernedorp” because of this; however Arderne apparently soon sold off all of these properties when in dire financial straits. (9) (He was the son of Ralph Henry Arderne, who had settled in Claremont in 1837 and established a magnificent garden on his estate, “The Hill”, just off the main road – today the Arderne Gardens. (10)) At the same time, Claremont Main Road was also developing rapidly as a commercial centre attracting more and more people into the area and in 1883, both upper and lower Claremont had been incorporated into the newly formed Liesbeeck municipality along with Newlands, Rondebosch, Wynberg and Mowbray. (11) (The idea behind this being the possible improvement of the water supply and the drainage system by combining in a bigger group) (12). The village of Claremont was apparently never happy in this union and after vigorous public meetings, Claremont became a separate municipality in 1890 with C.S Powrie as first Mayor, and finally a suburb of greater Cape Town in 1913.

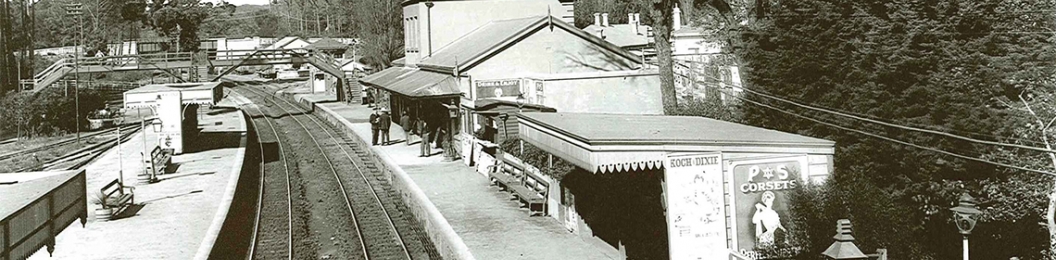

In 1931, Harfield Road Station along the southern suburbs line was opened to cater for the increasing working class population living around this particular area of Claremont. (13) Lower Claremont was becoming a popular area in the mid-twentieth century as it was near to a network of cheap busses and trains providing easy access to work. It proximity to the commercial hub that was Main Road in Claremont was also a draw-card. In Harfield itself, there was a self-sufficient infrastructure of over 40 shops and small businesses, some of which had been established for over sixty years and shopping in the area was convenient. (14) Second Avenue especially had many shops – a dairy, fish shop, butcher, shoemaker and “a tailor in every fourth house.”(15) Hawkers set up their fresh produce on the corners and a fish-smoking factory even operated from someone’s backyard. There were two well known corner shops / general dealers, one owned by Mr. Ali in First Avenue and the other by Mr. Sonday, further down the road. (16) Many residents operated “home-industries”, selling a variety of products to their neighbours. An abundance of schools, including the prestigious Livingstone High School (est. 1926), a number of primary schools and the Janet Bourhill Institute added to the appeal of the area as did a well-established network of places of religious worship. Both St. Mathews’ Anglican Church and the Methodist Church were in Second Avenue, St Ignatius Catholic Church was in Lansdowne Road and the Dutch Reformed Church was in Durham Street where the Zionists held their services every Saturday afternoon. Muslims worshiped at the Mosque in Harvey Road or Stegman Road, or else at the Claremont Main Road Mosque. For the Christian and Muslim communities, the church and the mosque were the focus of both their spiritual and social lives.

The population was a mixed one comprising of coloured, black, white and Indian residents, but the majority were coloured. (17) By the end of the 1960’s, the area was home to approximately 19 000 people and was one of three such “mixed” pockets within the broader white residential suburb of Claremont. (18) Above the railway line, a mixed community had developed around Draper, Protea and Vineyard Roads. Residents of this slightly more affluent area apparently looked down on their neighbours in lower Claremont who in-turn regarded themselves as being better off than the third mixed area below Rosmead Avenue, which was a very poor area, often referred to as “die Kas” or the Ghost Town (now known as Claremont Village). The community of lower Claremont was made up of people from all walks of life and in addition to the working class sector which included tradesmen, artisans, council workers, factory workers, domestic workers and so forth, there were also professional people such as lawyers, doctors and teachers living in the area. In addition, some prominent musicians, sports people, artists and politicians also called the area home.

Some of these families owned their own houses but many others rented – either from private land-lords or from the City Council. The area did however have a distinct working class character and some parts were regarded by other residents as being ‘slum-like’ in character. The “Langry” in Durham street – a row of terraced houses where families cooked, washed, dressed and ate in one room – was apparently one such area. The demand for accommodation was high and so two or three families would usually share one house which was generally a small semi-detached cottage with a corrugated iron roof. Very few had electricity or running water and provision for sanitation was often poor. In addition, very few of the absent landlords spent any money on the upkeep of their properties in this working class area. In order to supplement their incomes, tenants sometime sublet their backyards and allowed people to erect iron and wood shacks. It was also common for families and relations to live close together which enhanced the area’s community spirit.

Oral evidence about this period in Harfield’s history suggest that despite the poverty and the slums, the area was an “energetic” and dynamic place, characterised by close contact between neighbours and a sense of community spirit. (19) According to one resident, “we all mixed together, coloureds, whites, blacks, Christian and Muslim”, while another remembered, “we stayed together like a family, like a very close family – we grew up in front of these people and they recognised us, like one of their own, and even today when we meet then we are so glad.” (20) Children were taken care of by extended networks of friends and family while their mother’s worked during the day and the existence of shops that were owned by people who lived among the community meant that people were able to buy “on tick” (credit) when times were tough because they were so well known to the shop owners. Intermarriage in the community, as young people met at the local schools or in communal street areas, further strengthened the bonds between neighbours and residents remember that no-one was excluded from the celebrations, whether Christian or Muslim. As one of the shop keepers recalled; “Things were more personal than they are now. We used to play soccer together, eat together. It was a very cosmopolitan area. Blacks, whites, coloureds, Indians … when there was a wedding, everyone used to go. When there was a funeral, everyone used to cry. It was a very dense area.” (21)

In the evenings, when the work was done, there was always plenty to do. Dances with live bands were held often, either in private houses or in local halls, and both coloureds and whites attended. Afterwards, everyone would walk back together to their houses in the early hours of the morning. (22) Sunday afternoon jazz sessions were held at a house in Princess Square while another resident organised the “Swifts” dance club at his mother’s house in Durham Street, nick-named the “tickey bop” club because entry was so cheap. Pop’s Shebeen in Second Avenue, behind Livingstone High School, was a popular meeting place and a rehearsal spot for members of the community taking part in the “Klopse Carnival” which was the annual parade of minstrels singing and dancing through the streets of Cape Town to commemorate the freeing of slaves. (23) Each major street in lower Claremont had its’ own troupe that could be identified by the particular colours of their uniforms. The “Princess Square Swingsters”, an African musical group enjoyed much popularity in the area during the 1940s until the members of the choir were forced to move to Gugulethu in 1958, where the choir was fortunately reformed with some of the previous members. Sport was another cohesive social force and many exciting matches were held at the Rosmead grounds, a central sports facility (behind present Spar). As well as being a cohesive factor, sport also apparently encouraged healthy competition between the different parts of Claremont, so that many budding sportspeople were compelled to achieve. A local cinema, “The Orpheum” provided for local entertainment, as did the “Mathew-Rama”, a weekly bioscope begun in 1957 at St. Mathew’s Anglican Church in order to raise funds for the church. (24) Residents made use of a local public swimming pool for many years before it was closed following the construction of the Newlands Swimming pool, which unfortunately did not allow “non-whites” to have access. (25)

Despite the positive cultural capital that existed in the area mentioned above, there were also divisive issues in the community and some old residents are able to recall the bad along with the good. There were some areas where an elderly resident would not walk, especially the little back alleys which she remembered being strewn with rubbish. She recalled, “You could smell the dagga all over Claremont. There was a lot of domestic violence, men abused their wives and children. People today fantasize about their youth. But it wasn’t only pretty stories.” (26) Another resident remembers that the common denominators in lower Claremont were poverty and alcohol. (27) Gangs also had a presence in the old days – there were the “Spoilers” on First Avenue, the “Jungles” on Second Avenue as well as the Billiard Room Gang and others who gathered to gamble and fight on street corners, fist-fights that were usually quickly broken up by the arrival of the police. But because the community was a fairly stable one and because most residents knew each other, oral testimony indicates that the gangs did not cause too much trouble. For instance, one resident remembered, “The gangs were always respectful. They knew you and they were not violent or vicious … they were not out for killing. Their main concerns were about dagga, drink, girls, money and gambling. If you greeted him properly and spoke to him respectfully, he would respond.” Another remembered, “a skollie in those days was a decent skollie, he only interfered with you when he was drunk.” (28) A story is told of the Reverend Green of St. Mathew’s Anglican church, a man with a boxer’s physique who not only disciplined the male members of his congregation who drank too much, but whose appearance on his bicycle in the streets during the early 1930s was enough to send the gangs gambling on the street corners running, leaving their coins behind which the good reverend would then collect, pray over and proceed to use for the building of God’s kingdom. (29)